A Glimpse of My Own Mortality - Dr. Shantanu Abhyankar

Preface

Dr. Shantanu Abhyankar and I graduated together from Sanjeevan Vidyalaya in 1979. His passing away this month has left another big void in my life, after losing my father just a few days earlier. Though our paths diverged after school, our friendship remained undiminished by time or distance. Whenever we met, it was as if no time had passed at all, our connection as strong as ever. Shantanu's journey through his cancer diagnosis is a testament to his strength, intellect, and humanity. As his classmate and friend, I am honored to share his powerful story. This is a translated and summarized version of the original blog post on his blog

A Glimpse of My Own Mortality - Dr. Shantanu Abhyankar

It began innocuously enough - a persistent low-grade fever each evening, hovering between 98-99°F, accompanied by mild body aches. Nothing more. No cough, no cold, just those two symptoms dogging me day after day. Being a doctor, I made the classic mistake of many in our profession - I ignored it completely, powering through my days with Crocin one day, Combiflam the next.

Two grueling weeks passed, the pattern unyielding. Fatigue began to seep into my bones, an insidious whisper that something wasn't right. Reluctantly, I subjected myself to a battery of tests, each one coming back frustratingly normal. My "fever specialist" friend, exasperated, asked what I'd prescribe to a patient in my shoes. "Five days of antibiotics," I admitted sheepishly. "Then take your own damn advice," he shot back, my words a bitter pill to swallow. I did as instructed, but it made no difference. The fever, my constant companion, persisted.

More tests followed, more normal results. We grasped at straws - maybe Rickettsia? A course of doxycycline proved futile. Six long weeks had passed, each day a battle against my own body. One day, I barely managed to complete a surgery, every ounce of my strength drained, leaving nothing for my usual rounds. The fever, which had taunted me with a brief retreat, spiked to 100°F. Exhausted and desperate, I stumbled into a major hospital, placing myself under the care of an old classmate.

They redid every test, skeptical of results from my small-town labs. Yet the outcome remained maddeningly the same: all tests normal, while my body screamed that something was terribly wrong. I could see the doubt in their eyes - was this all in my head? But the stubborn thermometer didn't lie, and my haggard face told the story my words couldn't.

A "fever specialist" interrogated me for an hour, leaving no stone unturned. Had I examined other feverish patients? Any animal bites? Exotic foods? Swam in strange lakes? Entered mysterious caves? It felt absurd, like I was the cursed hero in some fantastical tale. But we pressed on, considering everything from TB to blood cancers, thyroiditis to endocarditis.

Being doctors ourselves, my wife and I pushed for more tests, cost be damned. We knew in our hearts this wasn't something minor. For the first time in my career, I had to abandon my patients, my duty. Little did I know how close I was to abandoning everything.

The PET-CT scan results were a gut punch. There I was, a shadowy figure with what looked like twinkling lights dotting my limbs. It was ominous, each light a beacon of dread. Most likely, a cancerous tumor in my lung - about the size of a plum. It hadn't crossed its initial borders, but it had spread insidiously to my neck, mediastinum, spine, and limbs. The other possibility was lymphoma, a blood cancer that presents similarly on a PET-CT. Either way, my world had shifted on its axis.

A biopsy confirmed the worst - lung cancer, not lymphoma. Even after the diagnosis, I remained surprisingly calm, a surreal detachment settling over me. I had suspected it might be something serious. What choice did I have but to face this new reality head-on?

My medical friends rallied around me, forming a WhatsApp group to discuss the latest diagnostic and treatment options. They debated sending samples to America, bringing me to Mumbai, and sourcing experimental medications. Their dedication was touching, a lifeline of hope in a sea of uncertainty.

Strangely, I skipped the typical stages of grief - denial, anger, bargaining. Instead, I moved straight to acceptance, my mind clinically assessing my new reality. I made my wishes clear: no emotional, futile treatments that merely prolong life. Ensure a peaceful, painless, and dignified death. If possible, donate my body without religious ceremony. The words felt alien on my tongue, yet necessary.

We had frank, often painful discussions about mortality. How much you live is important, but how you live is far more significant. We celebrated my son's birthday in the sterile hospital room, though the realization that I might not see many more hit me like a physical blow. The tears we shed that day were both bitter and sweet.

I didn't waste time asking, "Why me?" There's no divine justice ensuring good things happen to good people. Modern medicine seeks to understand the causes - agent, host, and environment. In my case, some retrograde planets in my genetic horoscope must have planted the message of 'misbehave' in my cells. It was easier to accept this scientific explanation than to rail against an uncaring universe.

My friend suggested genetic sequencing to identify specific defects in the cancer cells. This could lead to targeted therapies with minimal side effects. It would take three agonizing weeks to get the results, but it offered a glimmer of hope in the darkness.

That night, I experienced my first bout of severe cancer pain. It was unlike anything I'd ever felt, a searing agony that made me understand why people fear this disease so much. Four types of medication, including morphine, were needed to control it. We started chemotherapy while waiting for the genetic results, each infusion a battle against my own rebellious cells.

Despite the gravity of my situation, humor and friendship proved to be powerful medicine. My hospital room often buzzed with laughter and chatter from visiting doctor friends. There's no better immune booster than friendship and laughter, even in the face of death.

I decided to be open about my diagnosis, seeing it as an opportunity for cancer awareness. However, I learned a tough lesson about considering others' mindsets when sharing such news. After nearly shocking an acquaintance into a second injury with my blunt disclosure, I realized that even as a doctor, I had much to learn about the delicate nature of such conversations.

Well-meaning advice and alternative treatments poured in from all directions. People shared stories of cancer survivors, recommended exotic fruits and spices, suggested spiritual practices, and assured me that my "good karma" would see me through. While sometimes overwhelming, I recognized the love and concern behind these gestures, each one a testament to the connections I'd forged throughout my life.

Surprisingly, medical opinions from Chennai to Mumbai to the US were largely in agreement about my treatment. This consistency was reassuring and reflected the global standardization of cancer care protocols. Yet it also underscored the gravity of my situation - there were no miracle cures hiding in far-off places.

The shock of my diagnosis rippled through my professional network. Many struggled to process that this could happen to a relatively young, practicing doctor. It became easier to communicate through intermediaries rather than directly, the weight of mortality too heavy for some to bear.

As we awaited the genetic test results, I grappled with the financial realities of cancer treatment. The prices of targeted therapies were staggering, each pill a small fortune. I had to balance the desire to fight with the need to avoid financially ruining my family. It was a cruel equation, weighing the value of my life against the future security of those I love.

I sought advice from a palliative care specialist, asking tough questions about survival rates and quality of life. Her direct, honest answers were exactly what I needed, a beacon of truth in a sea of uncertainty. We agreed that for now, treatment made sense as it could restore me to a productive life. But we also acknowledged that this calculus might change as the disease progressed, a sobering reminder of the road ahead.

Throughout this journey, I've tried to maintain a clear-eyed view of my situation. There's a vast gulf between making resolutions and following through on them when faced with mortality. My hope is to bridge that gap, continuing to write honestly and transparently about this experience until the end.

If one can truly witness the ceremony of their own death, perhaps this is the way to make it meaningful. In sharing my story, I hope to shed light on the human experience of facing mortality, not just as a doctor, but as a person grappling with the ultimate unknown.

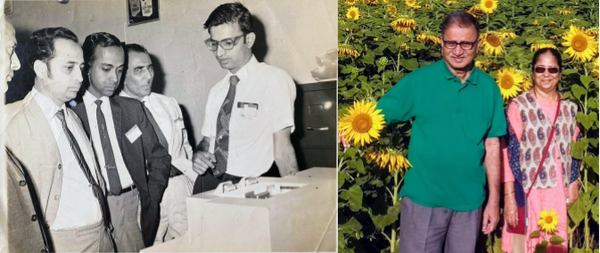

A Short Profile of Dr. Shantanu Abhyankar

Dr. Shantanu Sharad Abhyankar was a remarkable individual who wore many hats throughout his illustrious career. A distinguished medical professional, prolific writer, and passionate activist, he left an indelible mark on both his local community and the broader intellectual landscape of Maharashtra.

Born into a family of doctors, Shantanu followed in their footsteps, earning his MBBS from BJ Medical College in Pune before specializing in Obstetrics and Gynecology. However, his vision extended far beyond the confines of urban medical practice. Establishing the 'Modern Clinic' in Wai, he dedicated himself to bringing cutting-edge medical technology and techniques to rural communities, often innovating to meet the unique challenges faced by his patients.

Abhyankar's intellectual pursuits were not limited to medicine. A voracious reader and thinker, he authored numerous books on topics ranging from women's health to scientific reasoning and atheism. His works, including "Pali Mili Gup Chilli" and "Aadhunik Vaidyakichi Shodhgatha," reflected his commitment to spreading knowledge and promoting rational thought. This dedication to reason extended to his personal life as well, where he advocated for court marriages and non-traditional ceremonies, living his beliefs with conviction.

As a leading voice in the atheist movement and a trustee of various educational institutions, Abhyankar tirelessly worked to promote scientific thinking and combat superstition. His multifaceted personality shone through in his passion for theater and poetry, making him a true Renaissance man of modern Maharashtra. Even when faced with a cancer diagnosis in his final years, Abhyankar approached his illness with the same rational, positive outlook that had defined his life's work. His legacy lives on not only in his medical contributions and literary works but also in the countless lives he touched and minds he opened throughout his remarkable journey.