Learning to See

I've been learning to sketch on my iPad. What I didn't expect was a lesson in how I see the world.

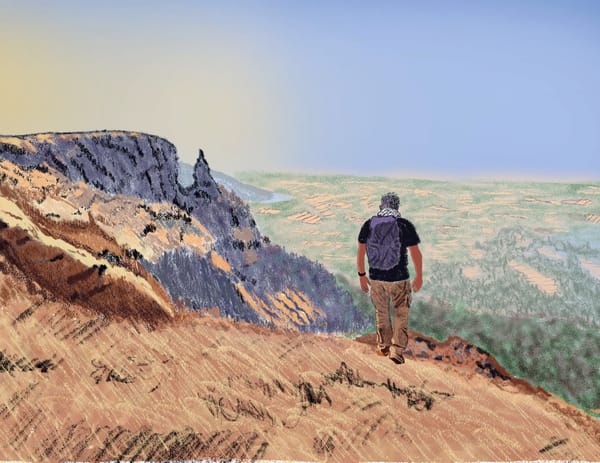

This piece combines two photographs from my daily morning walks in Mumbai to the hospital. One captured a tree-lined sidewalk on the road to the hospital. The other featured a pink flowering vine spilling over a hedge in the hospital where I was spending time attending to a medical emergency. The sketch in this post is an expression of hope I felt when I saw a ray of sunlight illuminating my path after long and tense days of waiting in the hospital.

The Problem: We See What We Believe

While making these sketches, I learned something new. I learned to see better.

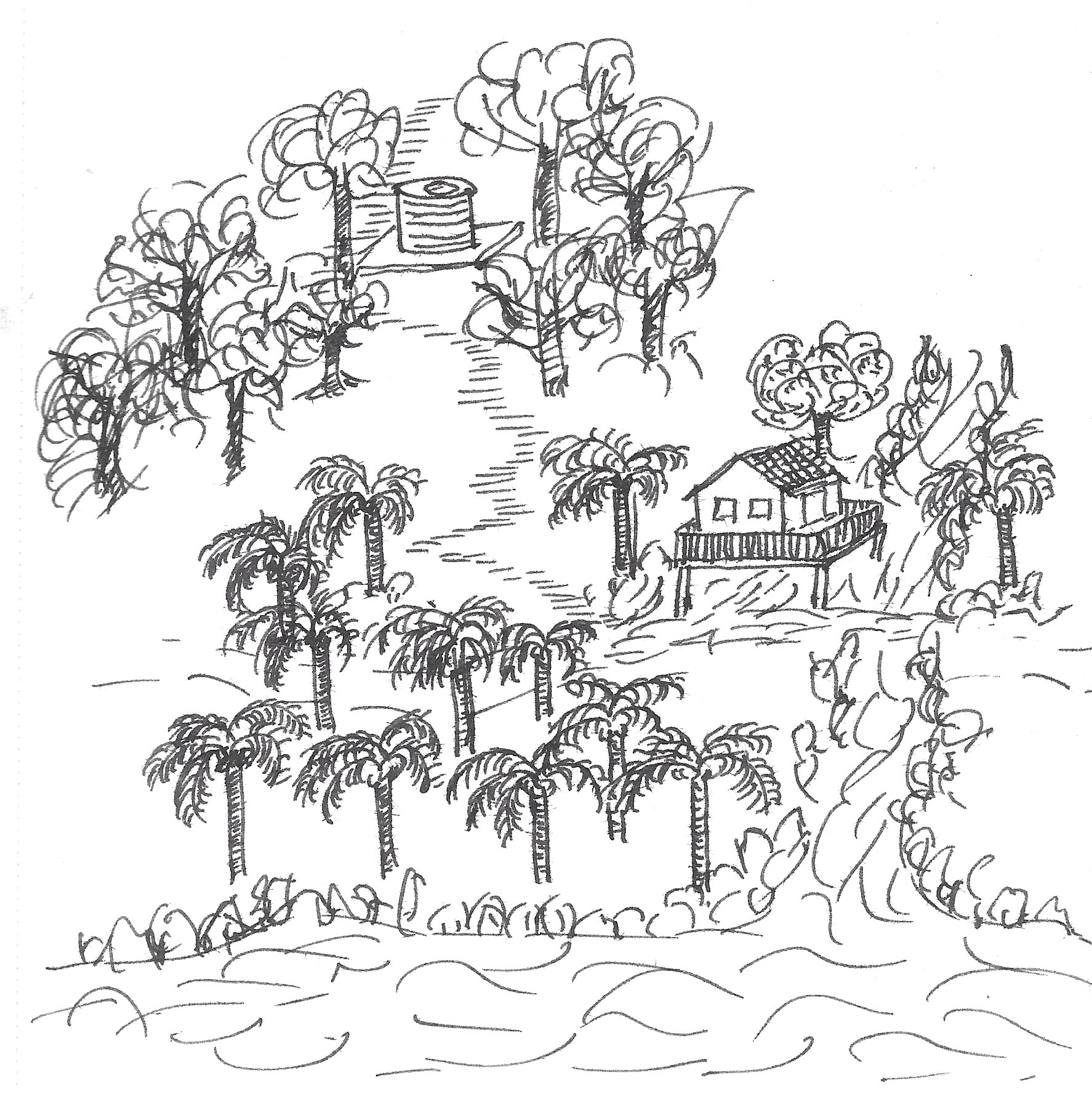

Earlier, when I tried to draw a tree, my mind said "tree" and immediately retrieved a symbol. Something I must have learned in childhood. A brown trunk. A green cloud on top. Maybe some lines for branches. I did not draw what's in front of me. I drew what I believed a tree looks like. You can see this from a sketch I made a few years ago of my farm.

This process is efficient. The brain is a pattern-matching machine, and abstracting the world into symbols is how we navigate it quickly. We don't need to analyze every tree we pass. We just need to know that it's a tree and move on.

But when you try to render what you see, to put it on paper or screen, this efficiency becomes a trap. The symbol stands between you and reality.

The Shift: Seeing Patterns, Not Objects

The breakthrough came when I stopped seeing objects and started seeing colors as geometric patterns.

A tree in morning light isn't a tree. It's a collection of shapes: dark masses where the canopy is dense, scattered bright spots where light punches through, warm patches on the trunk where sunlight hits, cool violet shadows on the ground.

That flowering hedge isn't "pink flowers on green leaves." It's clusters of magenta shapes punctuated by dark gaps, with yellow-green forms cascading behind.

When I stopped naming things and started seeing the form, the actual shapes, values, and edges, the sketches came alive.

Two Scales of Seeing

But there's the nuance: this practice operates at two different scales, and both are necessary.

At the macro level, the mind wants to combine the entire scene into a narrative: "a tree-lined street with flowers." The practice is to see the large shapes of light and dark as abstract compositional forms. Not as a scene, but as a pattern.

When I shared this idea with a friend who is a trained artist, she immediately recognized it and introduced me to the traditional technique of squinting. Squinting at your subject blurs the details and reveals the underlying value structure. It's a way to bypass the mind's labeling and see the large masses of light and dark. This concept, called "massing values" in classical instruction, addresses exactly what I was discovering at the macro level.

At the micro level, the mind wants to combine granular details into object-parts: "those are leaves," "that's bark," "those are petals." The practice here is almost the opposite of blurring. It's attending to each color patch, each edge, each shadow as its own shape, without letting the mind stitch them into the object they belong to.

| Scale | The mind's tendency | The practice |

|---|---|---|

| Macro | Combine scene into objects and narrative | See large value shapes as abstract forms |

| Micro | Combine details into object-parts | See each patch and edge as its own shape |

Both are acts of resistance against the same underlying tendency: the mind's rush to synthesize and label. One isn't sufficient without the other. Macro alone gives you structure but loses texture and specificity. Micro alone gives you detail but can lose coherence.

The complete practice is holding both simultaneously. Zooming out to see the pattern of the whole without naming the scene. Zooming in to see each granular shape without naming the object.

In the Mumbai street sketch, this meant:

- Macro: The scene became an arrangement of large dark and light masses. The canopy as one shape, the sidewalk as another, the foliage on the left as a third. Only later did it become "a street."

- Micro: Within that canopy, each dappled patch of light was its own specific shape. Not "sunlight through leaves" but this yellow-green polygon, that dark gap, this particular edge.

This is what artists mean when they talk about "learning to see." It's not mystical. It's the discipline of bypassing the mind's tendency to abstract, at every scale, and instead attending to what is actually present.

What the Literature Says

After my conversation with my friend, I became curious. If squinting was an established technique, what else had artists and teachers articulated about this challenge of seeing? I went looking for what the existing literature had to say.

What I found was validating. Artists have been wrestling with this problem for centuries.

Betty Edwards, in her 1979 book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, called these mental shortcuts "symbol systems." She observed that the verbal, categorizing part of our brain interferes with our ability to perceive. Her framing matched my experience precisely: the problem isn't the hand, it's the mind's insistence on labeling (ref).

Notan, a Japanese aesthetic concept meaning "light-dark harmony," treats shadow and light not as properties of objects, but as abstract shapes forming a balanced composition. When you reduce a scene to just black and white, you're forced to see the pattern rather than the thing casting the shadow (ref).

Classical painting instruction has long emphasized "massing values," the practice of grouping the infinite gradations we see into a few distinct shapes. The squinting technique my friend mentioned appears across centuries of art teaching (ref).

| Tradition | Core Teaching | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Betty Edwards (1979) | The verbal brain substitutes symbols for observation | Both |

| Notan (Japanese, popularized 1899) | Light and dark as abstract shapes, not object properties | Macro |

| Classical Value Massing | Squint to see the structure beneath the detail | Macro |

What struck me was how validating it felt to find these ideas articulated by others. The core insight, that the mind's efficiency in labeling becomes an obstacle to perception, appears across traditions. Betty Edwards in particular addresses both scales of the problem. The micro practice I had stumbled onto, attending to each granular detail without synthesizing it into an object, was not something I invented. It was something I rediscovered. And perhaps that's the nature of these perceptual truths. Each person has to find them for themselves.

The Life Lesson: What Else Are We Not Seeing?

If the mind does this with trees and shadows, substituting a quick symbol for actual perception at both the broad and granular level, where else is it doing the same thing?

With people.

At the macro level, we meet someone and immediately pattern-match their role, their category, their "type." How often have you felt the need to ask someone you meet the question - "So what do you do?" - as if knowing that will help us to get to know the person better. The symbol stands between us and the actual person.

At the micro level, we stop noticing the specifics. The particular way they pause before answering. The exact shade of hesitation in their voice. We've already filed them; why keep looking?

With situations.

At the macro level, something happens and the mind rushes to categorize: "this is like that time when..." When you hear someone tell you about their experience, we tend to map that experience to our own, and more often that not, start thinking about our own experience rather than listening to what actually happened to the other person. We respond to the pattern, not the instance.

At the micro level, we miss the granular details that make this situation different from all the others we've filed it with. Distinguishing those minute details helps learn and identify new ideas. If we are busy matching patterns, we will never discover new things, I feel.

With ourselves.

At the macro level, we carry narratives about who we are. Our capabilities, our limitations, our identity. We practice our "pitch" to the world and try to live by it. I am after all, a mathematician and a software architect. I cannot be talking about sketching and art! These predefined identities drive our lives and we just keep doing the same things again and again, rather than learning new things to do.

At the micro level, we stop noticing the small, specific moments where we're actually different from our story. We often try and match up to some ideal definition of who we are supposed to be, rather than celebrate the oddities and nuances that make us unique.

The same mental efficiency that makes us functional also makes us blind. At every scale.

A Question About AI Art

And what about AI Art? AI image generators are, at their core, pattern machines. They have ingested millions of images and learned what things "look like." When asked to generate a tree, will they produce something derived from the averaged pattern of all the trees they've seen.

The AI, in a sense, is the symbol system. It generates from learned patterns. It doesn't attend to a particular subject because there is no particular subject in front of it. There is only the prompt, and the vast library of patterns the prompt activates.

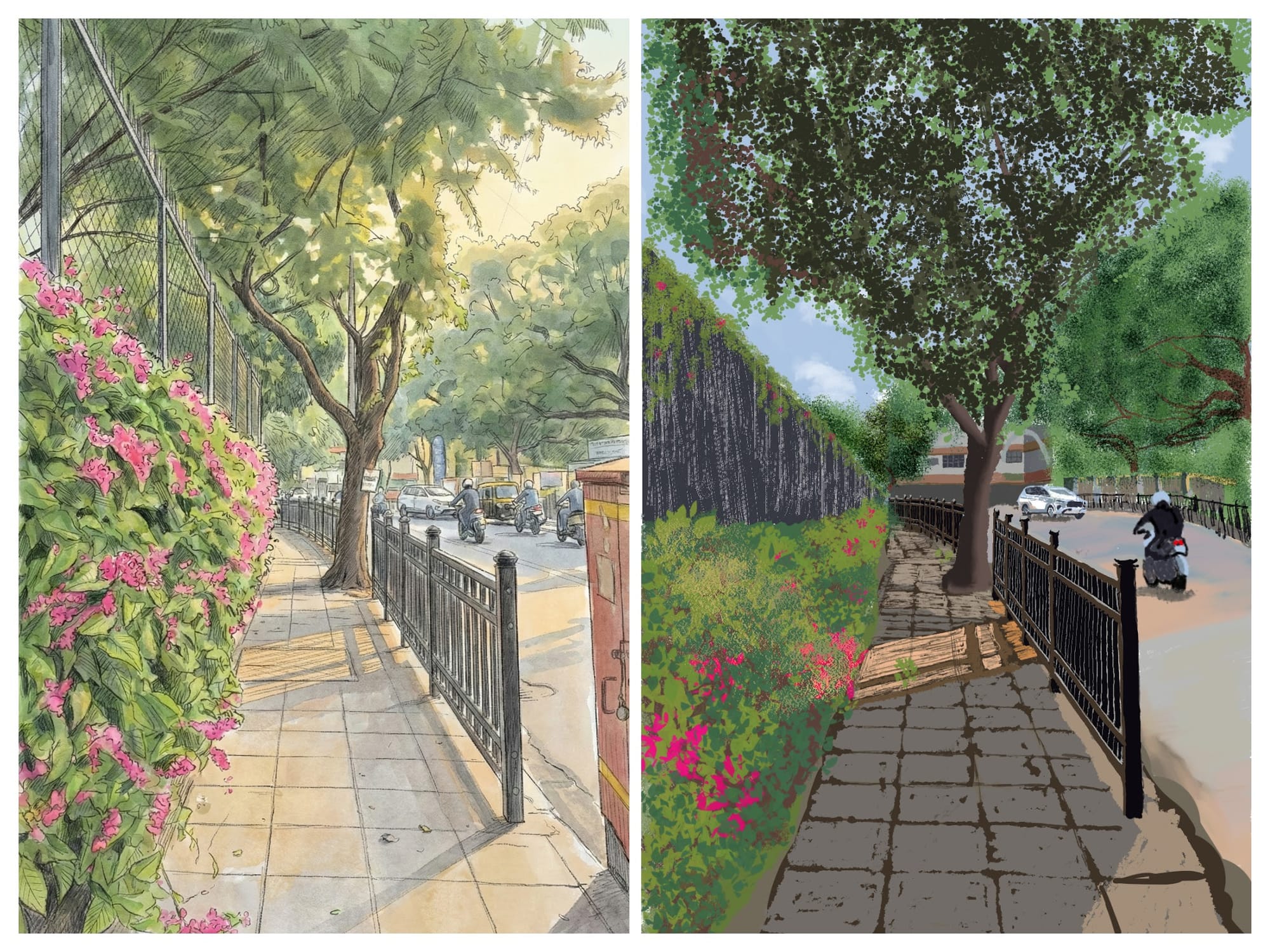

Of course, I also tried constructing the sketch using Nano Banana by adding both my photos and prompt to describe how I wanted to combine them, and it did a pretty good job - as you can see below. It captured all the details from the photographs and my prompt. But did it capture my emotion of seeing a bright ray of light illuminating my path after a several days of tension in a hospital waiting room?

I don't have an answer. But I find the question useful. It suggests that the practice of actual seeing, the discipline of attending to what is present rather than what the pattern-library suggests, may be something distinctly human. Or at least, something that humans must cultivate precisely because our minds, like AI, default to patterns.

An Ongoing Practice

I don't think the answer is to abandon abstraction entirely. We'd never get through a day. But perhaps there's value in cultivating moments of actual seeing. Dropping the symbol. Attending to the form. At both scales. This is not a skill I've mastered. It's a practice I've begun.

The Mumbai street sketch was an exercise in combining two photographs. But the real exercise was in attention. Training myself to see the pattern of light through leaves, the geometry of shadows on stone, the shapes that my mind wanted to skip over in its rush to label and move on.

I suspect this practice never ends. The mind will always reach for its shortcuts. The discipline is in the moments we choose to set them aside.

What patterns are you not seeing?