The Inverted Value Pyramid

A Technologist's Reflection from an RTO Queue

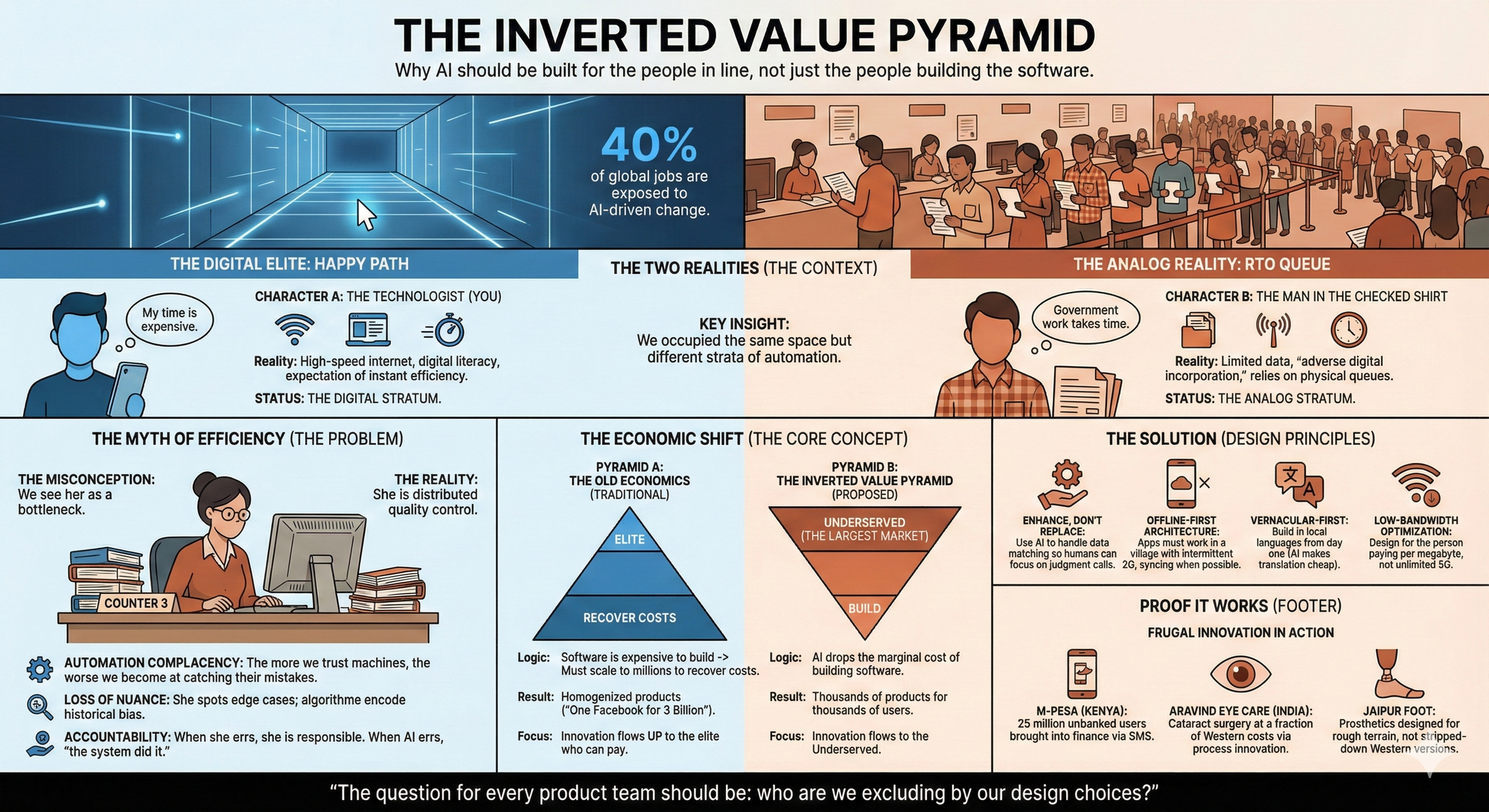

Building AI for the billions left behind, not just the millions already ahead.

TL;DR (30 seconds)

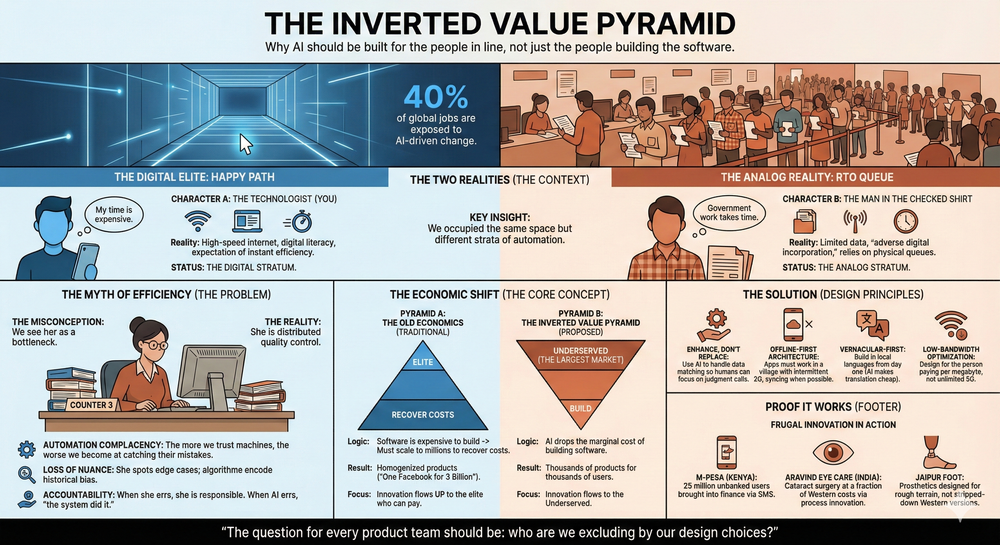

Standing in an RTO queue, I watched a woman at the counter squint at her monitor, verifying documents one by one. My instinct was to see her as the bottleneck. But she's actually the quality control we don't see. The human checkpoint that catches what algorithms miss. And yet our efficiency-obsessed solutions will likely make her obsolete without offering anything in return. We have the technology to serve billions who remain in analog systems. Offline-first architectures, voice interfaces, SMS-based services. We just treat them as edge cases instead of primary design constraints. What if we inverted that?

TL;DR (2 minutes)

The RTO queue revealed two invisible structures: strata of automation (the layers of who benefits from digital systems and who remains in analog workflows) and the inverted value pyramid (what happens when we design for the underserved first, not last).

Two realizations emerged:

First, the woman at Counter 3 isn't the problem. Research shows that the more we trust machines, the worse we become at catching their mistakes. The multi-step manual process isn't purely dysfunction. It's distributed quality control. We didn't invent human-in-the-loop. Bureaucracy did. Her decades of experience handling edge cases represent institutional knowledge, not inefficiency. Replace her with an ML model and you risk encoding biases into decisions. And yet, about 40% of global jobs are exposed to AI-driven change according to the International Monetary Fund [1]. The jobs being created require master's degrees. The jobs being destroyed don't.

Second, we have the technology to enhance her judgment, not replace it. AI that understands natural language can help her do what she already does well, faster. But we didn't build that. We digitized without redesigning. "User centric" remained a buzzword.

The economic shift: Software used to be expensive to build, so we built one product for millions. That forced us toward scale, toward homogeneity, toward users who could pay. But AI is dramatically reducing the marginal cost of building software. What if we could build a thousand products for what one used to cost? Each deeply tailored to specific user groups, designed for their constraints?

The proof: M-Pesa brought about 25 million unbanked Kenyans into financial services using SMS. Aravind Eye Care performs cataract surgery at a small fraction of Western costs. These succeeded as ground-up designs for different constraints, not stripped-down versions of rich-world products.

The inverted value pyramid asks: who are we excluding by our design choices? And now that the economics have changed, what's our excuse?

The Queue

Token number 847.

I was at the Regional Transport Office in Mumbai, there to submit an application for a duplicate registration certificate for my vehicle. The irony wasn't lost on me. I had already completed the entire process online. Filled the forms digitally. Uploaded scanned documents. Made the payment through a government portal. Received an acknowledgment number.

And yet, here I was. Physically present. Holding printouts of the very forms I had submitted digitally. Waiting to hand them to a human being who would verify what the system had already verified.

The RTO office was a study in controlled chaos. Multiple counters, each with its own queue. Counter 1 for document verification. Counter 3 for data entry confirmation. Counter 5 for the inspector's review. And finally, a small cabin at the end where the chief officer would inspect the file and apply the signature without which nothing could proceed.

I watched the process unfold with the particular frustration of someone who builds digital systems for a living. Each step seemed designed to maximize human touch points. Each queue a monument to inefficiency. Each signature a ritual whose purpose had long been forgotten but whose absence would halt the entire machinery.

The person standing next to me, a middle-aged man in a faded checked shirt, seemed entirely unbothered. He chatted amiably with others in the queue, checked his phone occasionally, and displayed none of the impatience that was gnawing at me. When I muttered something about the wait, he shrugged. "Government work takes time," he said, as if stating a law of nature.

That's when it struck me. We were standing in the same physical queue, but we were living in entirely different temporal economies. My time was expensive, or at least I had convinced myself it was. His time operated on a different calculus altogether. The hours spent here weren't stolen from him the way they felt stolen from me.

We occupied the same space but different strata of automation. By that I mean the invisible layers of technological access - who benefits from digital systems and who remains stuck in analog workflows, who can skip the queue and who must wait.

And as I watched the woman at Counter 3, thick glasses perched on her nose, peering at her monitor with the intensity of someone deciphering an ancient script, I began to wonder about the assumptions I carry as a technologist. About efficiency. About progress. About who we build for and who we leave behind.

Part I: The Woman at Counter 3

She was perhaps in her fifties. Government employee, clearly. The kind who joined decades ago when a public sector job was the pinnacle of middle-class aspiration. Steady salary. Pension. Respectability.

Her thick glasses suggested years of close work. Her posture, hunched slightly toward the monitor, suggested someone for whom screens remained somewhat foreign. Tools to be wrestled with rather than extensions of self.

She was the human interface between the digital system and the analog process. Data came to her on screen. She verified it against the physical documents. She typed entries, clicked buttons, moved applications from one status to another.

My first instinct was to see her as the problem. The bottleneck. The reason I was waiting.

But watch her work for a few minutes and something else emerges.

The Hidden Value of Human Checkpoints

There's a concept in automation research called "automation complacency." It describes what happens when humans become passive consumers of AI outputs rather than active validators.

A 2024 study published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior examined how different formats of AI assistance influence human performance over time. The finding was sobering: initial reliance on direct AI answers impaired performance on subsequent tasks when the AI made errors [2].

In other words, the more we trust the machine, the worse we become at catching its mistakes.

Consider what full automation of the RTO process might look like. AI reviews the application. AI matches the documents. AI approves the request. No queues. No waiting. No lady at Counter 3 peering through thick glasses.

Efficient? Absolutely.

But what happens when the AI makes an error? When it approves a fraudulent application because the documents were sophisticated forgeries? When it rejects a legitimate application because the photo quality didn't meet some algorithmic threshold? When it makes a decision that no human ever reviewed?

In the current system, frustrating as it is, there's a human at each step who can exercise judgment. Someone who can look at an edge case and say, "This doesn't fit the rules, but it makes sense." Someone who can spot something that feels wrong even if it looks right on paper.

The multi-step manual process isn't purely dysfunction. It's distributed quality control. Each counter in the RTO serves as a checkpoint. The document verification counter catches missing papers. The data entry counter catches typos and mismatches. The inspector's review catches fraud attempts. The chief officer's signature creates final accountability. In a system historically plagued by corruption and errors, this redundancy builds trust.

We didn't invent human-in-the-loop. Bureaucracy did.

The woman at Counter 3 isn't making the system slow. She's making it reliable. She's the quality control we don't see because we're too busy being frustrated by the wait.

And there's something else we overlook. She represents decades of accumulated experience. Hundreds of edge cases encountered and resolved. Thousands of judgments made about documents that didn't quite fit the standard pattern. This isn't inefficiency. It's institutional knowledge embodied in a person.

Replace her with a rules engine, and you lose the nuance. Replace her with a machine learning model trained on historical data, and you risk encoding biases into decisions that affect people's lives. ML models learn patterns from the past, including patterns of discrimination we'd rather not perpetuate. Her human judgment, refined through years of practice, can weigh context in ways that algorithms struggle to replicate.

The Missed Opportunity

But here's what bothers me most. We had another option.

Instead of building systems that would eventually replace her, we could have built systems that enhanced her judgment. Not a rules engine that forces her decisions into rigid pathways. Not an ML model that makes decisions for her based on patterns she can't see or question. But AI that understands natural language and helps her do what she already does well, faster and with less friction.

Instead of squinting at a badly designed application while cross-referencing paper documents, she could have a conversational assistant that helps verify information through natural dialogue. Instead of jumping between multiple windows, operators could work in parallel with AI handling data reconciliation in the background. The AI handles the tedious matching. She handles the judgment calls. Her experience remains central. Her decisions remain hers.

The technology exists. OCR can read documents. Natural language processing can guide verification. Intelligent workflows can route edge cases to the right people. We have conversational interfaces, offline-first architectures, vernacular language support.

But we didn't build that. We built systems that treat her as an obstacle to be routed around, not a professional whose judgment should be amplified.

How much more efficient did digitization actually make her day? She still verifies the same documents. She still makes the same judgments. She just does it while wrestling with software that wasn't designed with her in mind. The queue moved from outside the building to inside a waiting room. Progress.

The question we never asked: what if we designed for her constraints first? What if "user centric" meant the user at Counter 3, not the applicant with a smartphone and unlimited patience?

The Displacement Question

And yet.

What will happen to her when we fully automate?

The cruel mathematics of technological change: the jobs most likely to be automated are precisely those that provide stable employment to people without advanced degrees. Data entry. Document verification. Routine cognitive tasks. The work that lifted families into the middle class over the past few decades is the work most vulnerable to algorithmic replacement.

The jobs being created are not the jobs being destroyed. New roles demand master's degrees, fluency in English, comfort with abstractions. The woman at Counter 3 has none of these. She has something else: judgment refined through decades of practice. But the market doesn't know how to value that.

So I ask: what is she supposed to do?

The standard answer is "reskilling." Learn new skills. Adapt to the changing economy. Embrace lifelong learning.

It's an answer that sounds reasonable in policy papers and feels cruel in practice. This woman has spent a career mastering a particular set of tasks. She's perhaps a decade from retirement. She has family obligations, financial constraints, limited access to quality training.

And we're telling her to "reskill." As if learning machine learning in your fifties, while working full-time, with limited English proficiency, is equivalent to what a fresh engineering graduate does.

The question isn't whether to automate. It's whether we understand what we're automating deeply enough to preserve what matters while discarding what doesn't. And who bears the cost of our errors and our efficiency gains.

When a human clerk makes a mistake, there's someone to hold accountable. When an algorithm makes a mistake, accountability diffuses. "The system did it" becomes the explanation.

The burden of adaptation falls on those least equipped to adapt. The benefits of automation flow to those already advantaged. This is not a bug in the system. It's the system working exactly as designed.

How did we get here?

Part II: The Paradox of Partial Digitization

The RTO experience reveals something uncomfortable about how we digitize.

We haven't replaced the old system. We've layered a new one on top of it. The result is a hybrid that captures neither the efficiency of digital nor the accountability of analog. Before digitization, applicants would queue from 7 AM for counters that opened at 10 AM. After digitization? They still queue, just with printouts in hand.

We digitized the process without redesigning it.

We took paper forms and made them PDFs. We took physical queues and added online appointment systems. We took manual verification and put it on a screen. The workflow remained identical. The human touchpoints remained identical. We just added computers to each step. "User centric design" remained a buzzword in project documents. Nobody asked whether the woman at Counter 3 actually needed a clunky software interface that made her job harder. Nobody asked whether the process itself made sense in a digital world.

This pattern repeats everywhere. Organizations digitize to say they've digitized. They automate to say they've automated. The metrics look good on dashboards. But the humans in the system, both the workers and the people they serve, experience something far messier.

This doesn't mean we shouldn't digitize. It means we should redesign, not just digitize. And here's the thing we often miss: automation does not necessarily mean replacing humans. With AI that understands natural language, automation can mean human-machine collaboration leading to much higher levels of productivity without loss of security, privacy, or even jobs. The goal isn't to substitute human judgment with machine learning models that can encode biases we don't understand. It's to enhance human judgment with tools that handle the tedious parts while keeping people at the center of decisions that matter.

But this requires us to see the people we're building for. All of them.

Part III: The Strata of Automation

Let me return to the man in the checked shirt. The one who seemed unbothered by the wait.

His equanimity wasn't Zen-like detachment. It was something simpler and more structural. He exists in a different relationship with time and technology than I do.

I have high-speed internet at home and in my pocket. I have bank accounts and credit cards that let me transact digitally. I have the education to navigate online forms. I have the expectation, born of privilege, that systems should respond to my time constraints.

He may have none of these. Or he may have some of them, partially, precariously. The smartphone he checked might have limited data. The digital services available to me might be inaccessible to him through infrastructure gaps or literacy barriers or simple unfamiliarity.

Step outside the RTO for a moment and look at the macro numbers. The global data is stark.

According to a joint study by UNESCO, the International Telecommunication Union, and the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, about 2.7 billion people remain offline globally [3]. Internet access reaches 93% of the population in high-income countries. In low-income countries, that number drops to 27%. In the world's least developed nations, only about a third of the population has ever used the internet.

Within countries, the divide deepens. A 2024 report from the Brookings Institution notes that urban residents are twice as likely to be online as rural residents [4]. The young are far more connected than the elderly. The educated outpace the less educated. Men outpace women in many developing nations.

And this is just connectivity. Beyond access lies the question of meaningful use, what researchers call the gap between "universal connectivity" and "meaningful connectivity." Having a phone doesn't mean having the skills to use digital government services. Having internet access doesn't mean having the bandwidth for video tutorials or the data allowance for large file uploads.

The Brookings Institution describes a pattern called "adverse digital incorporation," a condition where digital inclusion happens under exploitative terms that actually deepen inequality [4]. You get access, but on conditions that extract more than they provide. You join the digital economy, but at its margins, vulnerable and precarious.

This is the world my queue neighbor inhabits. Not a world without technology, but a world where technology arrives unevenly, incompletely, often in forms designed for someone else.

I call these the strata of automation.

We don't all live in the same technological present. Some of us inhabit a near-future of AI assistants and automated workflows. Others live in a recent past of smartphones and basic apps. Still others, and they number in the billions, live in an analog present where paper forms and physical queues remain the only reliable interface with institutions.

The frustration I felt in the RTO queue was the frustration of someone whose stratum had been temporarily forced into contact with another. I was experiencing, briefly and voluntarily, what many experience permanently and without choice.

Part IV: The Incentive Problem

Here's a question I found myself asking as I waited: as a digital engineer, where should I direct my efforts?

Option A: Build tools for people like me. High-income knowledge workers who will pay premium prices for premium solutions. Productivity apps. Automation platforms. AI assistants that make the already-efficient even more efficient.

Option B: Build tools for people like the lady at Counter 3. Or the man in the checked shirt. Or the hundreds of millions who need technology but can't pay Silicon Valley prices for it.

The honest answer is that Option A is what the market rewards. And the market is what shapes most technological development.

Old economics: one product for millions

This isn't a moral failing of individual technologists. It's a structural reality. The current value pyramid works like this:

| Stratum | Role today |

|---|---|

| Elite | Primary target of innovation |

| Middle class | Growing market, increasingly well-served |

| Working class | Price-sensitive, partially served |

| Underserved | Largely excluded from design priorities |

Innovation flows upward because that's where the money is. Venture capital funds solutions for the top of the pyramid. Engineers are hired to solve problems for those who can afford to hire engineers. The entire ecosystem of technology development is oriented toward serving those who already have.

The result is visible in any app store. Hundreds of productivity tools for knowledge workers. Dozens of premium meditation apps. AI assistants for executives. And remarkably little for the driver who needs to navigate bureaucracy, the farmer who needs weather information, the small vendor who needs access to credit.

Yes, there are exceptions. Yes, there's work happening at the "bottom of the pyramid." But it's a fraction of the overall investment, a footnote to the main story of technology development.

And the feedback loop is vicious. Those with capital invest in automation that serves their interests. This increases their returns. Which gives them more capital to invest. Which further tilts innovation toward their needs.

New economics: thousands of products for thousands

But here's something we rarely question: the entire value pyramid rests on an economic assumption that may no longer hold.

Software is expensive to build. Or at least, it used to be. A product requires months of development, teams of engineers, rounds of testing. To recover those costs, you need millions of users. So you build one product and try to sell it to everyone. You target the largest possible market, which means you target those with money and connectivity and digital literacy. The economics force you toward the top of the pyramid.

This is why we have one Facebook for three billion people instead of thousands of community platforms. One Uber instead of hundreds of local transit solutions. One Salesforce instead of purpose-built tools for every type of business. The fixed costs of building drove us toward scale, and scale drove us toward homogeneity.

But what if building costs collapsed?

What if you could build a thousand products for what one product used to cost? What if each product could be deeply tailored to a specific user group, designed for their constraints, speaking their language, solving their particular problems?

The economics of the value pyramid would invert. Instead of one product for millions, you could have thousands of products for thousands. Instead of forcing users to adapt to software designed for someone else, you could build software that adapts to them.

This isn't hypothetical. AI is making it real. And it changes everything about the incentive problem.

So I return to my question. As a technologist, what is my responsibility?

Do I solve problems for those who pay most? That's what the old economics incentivized.

Do I solve problems for those who need most? The new economics might finally make this viable.

Part V: The Inverted Value Pyramid

So what does this look like in practice?

Instead of innovation flowing upward toward those who can pay most, what if we started with those who have been excluded?

| Stratum | Role in inverted model |

|---|---|

| Underserved | Primary design focus, largest untapped need |

| Working class | Next layer of tailored, constraint-aware tools |

| Middle class | Already well-served by existing products |

| Elite | Saturated market, marginal gains from new tools |

The top of this inverted pyramid isn't charity. It's the biggest untapped market in the world. Billions of people with real needs, real purchasing power (even if modest), and almost no products designed for their constraints.

The Product Opportunity

The economics have shifted. Building for small, underserved user groups now pencils out. Code generation accelerates development. Natural language interfaces become feasible without massive training datasets for each language. Conversational assistants can be deployed at a fraction of previous costs.

This opens up a different way of building products: low footprint applications, developed at rock-bottom cost, but designed to be deeply user-centric for specific small user groups. Not mass-market products dumbed down for the poor. Purpose-built solutions that treat constraints as the design brief.

And crucially, these are tools for collaboration, not replacement. Not rules engines that force rigid workflows. Not ML models that make opaque decisions. But AI that understands natural language and enhances human judgment.

Think about what this means for the woman at Counter 3. A conversational assistant that helps her verify documents faster, in her own language. An interface that surfaces relevant information without forcing her through twelve screens. A system that handles the tedious data matching while she focuses on the judgment calls that actually require her experience. Her decades of institutional knowledge remain central, and she retains authority over the final call. She just becomes dramatically more effective.

The goal isn't to eliminate jobs. It's to amplify the people doing jobs that matter.

Offline-first architecture. Data lives locally. Sync happens when connectivity allows. Conflicts resolve gracefully. The application remains fully functional whether you're in a Mumbai high-rise or a village with intermittent 2G. This isn't technically difficult. Tools like PouchDB, CouchDB, and dozens of sync frameworks make this straightforward. We just don't prioritize it.

Progressive enhancement. Start with the simplest possible interface that delivers value. Layer complexity for those who want it. An SMS bot that answers questions. A voice interface that guides users through processes. A simple web page that works on any browser. A rich app for those with capable devices. Each layer serves a different stratum without excluding anyone.

Vernacular-first design. Build in local languages from day one, not as translations bolted on later. Design interfaces that work with the idioms and mental models of local users. Test with people who aren't like us. With AI-powered translation and localization, this is no longer prohibitively expensive.

Low-bandwidth optimization. Compress aggressively. Cache intelligently. Prefetch what users are likely to need. Design for the person paying per megabyte, not the person with unlimited data.

Asynchronous workflows. Not everything needs real-time response. Design processes that tolerate latency. Let users submit requests that get processed when connectivity returns. Provide clear feedback about status without requiring constant polling.

The technology is ready. The patterns are established. AI has dramatically reduced the marginal cost of building tailored interfaces and workflows. What's missing is the will to make these approaches primary rather than secondary.

If the inverted value pyramid sounds idealistic, look at the places where this logic has already succeeded under far tougher constraints.

Proof That This Works

This isn't theoretical. The model has been proven, even before AI made it cheaper.

Consider frugal innovation, the practice of creating faster, better, cheaper solutions that serve more people in essential areas like healthcare, finance, and energy. The principle is simple: do more with less for more people.

M-Pesa in Kenya: An SMS-based mobile money service that enabled about 25 million unbanked Kenyans to send and receive money through basic phones. No smartphone required. No bank account required. Just a simple interface matched to the constraints of the users. The World Economic Forum has documented how this single innovation transformed financial inclusion across East Africa [5].

Aravind Eye Care in India: A system that performs cataract surgeries at a small fraction of Western costs without compromising quality. They achieved this through process innovation, an assembly-line approach that maximizes surgeon productivity while maintaining outcomes.

Jaipur Foot: A prosthetic leg designed for the conditions of rural India. Durable, affordable, functional in fields and on rough terrain. Not a stripped-down version of a Western prosthetic, but a ground-up design for a different context.

Power Blox in the Pacific Islands: The United Nations Development Programme has documented how these modular energy cubes work like Lego blocks, allowing communities to start small and scale their power grid as their needs and resources grow [6]. No massive upfront infrastructure investment required.

These aren't charity projects. They're sustainable businesses designed from the ground up for different constraints. They achieved scale and profitability that well-funded Silicon Valley ventures would envy.

The common thread: start with the constraints of the underserved, not the desires of the affluent. The constraint isn't a limitation to work around. It's the design brief.

Now imagine what becomes possible when building for those constraints costs a fraction of what it used to. When AI can generate vernacular interfaces. When conversational assistants can be deployed for thousands instead of millions. When small user groups become economically viable to serve.

The question for every product team should be: who are we excluding by our design choices? And now that the cost of inclusion has dropped, what's our excuse?

Closing: Back to the Queue

Token 847 was eventually called.

I moved through the counters, submitted my documents, collected my signatures, and emerged into the Mumbai afternoon with my duplicate registration certificate assured.

A small victory, if you can call it that. The system had worked. Slowly, redundantly, frustratingly. But it had worked.

As I walked out, I passed the woman at Counter 3. She was still there, still peering at her monitor, still processing applications one by one. Still wrestling with software that wasn't designed for her. Still providing quality control that nobody acknowledges.

I wondered about her future. Would we build systems that empower her, or systems that replace her? Would anyone ask what tools she actually needs, or would we just assume she's the obstacle to be automated away?

And I wondered about myself. About the systems I build and the assumptions embedded in them. About who I design for and who I leave out. About the strata of automation I inhabit and my responsibilities to other strata.

The man in the checked shirt was still there too, somewhere in the queue. Waiting with the patience of someone for whom waiting is simply what you do. Not because he lacked ambition, but because the temporal economy he inhabited didn't price his hours the way mine were priced.

We build technologies that save time for those whose time is already valued. We build efficiencies for the efficient. We optimize for the optimizers.

What would it mean to invert this? To build for those whose time is undervalued? To empower those we currently ignore? To design for constraints instead of dismissing them?

The inverted value pyramid isn't just policy. It's not just a business model or an economic theory. It's a question each of us must answer, individually, in the work we do every day.

Do we build upward, or do we build for all?

The lady at Counter 3 is waiting for our answer.

This essay was written while reflecting on the nature of automation, efficiency, and responsibility. The author is a technologist who has spent too many hours in government offices and not enough hours asking why those offices exist in the first place.

Key Statistics

For those who want the numbers:

Global AI exposure

- About 40% of global jobs exposed to AI-driven change, according to the IMF [1]

- About 300 million full-time job equivalents exposed to automation, according to Goldman Sachs [7]

- 77% of new AI jobs require master's degrees or higher [10]

Digital divide

- About 2.7 billion people remain offline globally [3]

- 93% internet access in high-income countries vs. 27% in low-income countries [8]

India's workforce

- 68% of Indian white-collar workers fear automation within 5 years (IIM-Ahmedabad study, cited in [9])

- 60,000+ workforce reduction at India's top three IT firms in FY 2023-24 [11]

Case studies

- About 25 million Kenyans empowered through M-Pesa mobile money [5]

References

[1] International Monetary Fund, "AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let's Make Sure It Benefits Humanity" (2024) - https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/01/14/ai-will-transform-the-global-economy-lets-make-sure-it-benefits-humanity

[2] "The efficiency-accountability tradeoff in AI integration: Effects on human performance and over-reliance," Computers in Human Behavior (2024) - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949882124000598

[3] UNESCO, ITU, and Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development, "State of Broadband Report" - https://www.broadbandcommission.org/publication/state-of-broadband-2023/

[4] Brookings Institution, "Fixing the global digital divide and digital access gap" (2024) - https://www.brookings.edu/articles/fixing-the-global-digital-divide-and-digital-access-gap/

[5] World Economic Forum, "Frugal innovation: the quiet revolution that is fighting off inequality" (2017) - https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/04/how-frugal-innovation-can-fight-off-inequality/

[6] United Nations Development Programme, "Frugal Innovation: An opportunity to democratise electricity" - https://www.undp.org/pacific/blog/frugal-innovation-opportunity-democratise-electricity

[7] Goldman Sachs, "The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth" (2023) - https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent.html

[8] International Telecommunication Union and UNESCO, "Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2023" - https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx

[9] "Psychological impacts of AI-induced job displacement among Indian IT professionals," PMC (2024) - cites IIM-Ahmedabad survey on white-collar worker perceptions - https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12409910/

[10] Nartey, J., "AI Job Displacement Analysis (2025-2030)," SSRN (2025) - https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5316265

[11] Bloomberg/India Dispatch, "Indian IT Outsourcing Firms Cut 60,000 Jobs in First Layoffs in 20 Years" (April 2024) - https://indiadispatch.com/p/indian-consultancy-firms-tcs-infosys-and-wipro-have-cut-over-60000-jobs-in-a-year